Tatreez is an Arabic word that translates to the word "embroidery" in the English language. In today's context, it is often used to refer to Palestinian embroidery, more specifically the cross-stitch technique.

The cross-stitch is practiced in many indigenous cultures across the world, and is not solely owned by any one in particular. Though, arguably, Palestinians have a high claim. What makes this stitch so unique to the Palestinian culture is not simply its historical origins in the region but also how Palestinians engaged with it over time, materialized it into their traditions, and wove it into their identity.

Pre-1948, Palestinian women used tatreez as a form of storytelling. This was especially the case for women who lived in village areas. Generally speaking, Palestinian women would observe their environments (like trees, flowers, and plants), and would create motifs or patterns to stitch into their thobes (Palestinian dress). They were, in essence, walking museums, of their surroundings.

Photo depicts a woman wearing a typical thobe from the Ramallah region from around the 1940's.

During this time, tatreez was traditionally learned, stitched, and worn in community and through family.

Girls would learn as young as five-years-old. They would begin stitching garments for themselves for when they reached an older age. They would wear these garments throughout their lifetimes, mending them as they went along.

Then, they would pass down their thobes through their family lineage to further preserve or as a form of inheritance. For some villagers of low economic status, this could have been done as a form of passing down clothing to be reworn.

Tatreez is a rich Palestinian craft that is incredibly time-consuming and labor-intensive. It may take months or years to finish just one garment, which is why women learned embroidery at such a young age. It required an entire community to sustain this craft—the young, the older, the women, and the men.

Tatreez is not solely a woman's craft. It is very much a man's craft as well. Men participated in embroidery as well as found their roles in weaving thread and fabric. They also played a huge role in selling these valuables in the markets.

As time went by, tatreez continued to manifest itself in the stories its people experienced. This is especially the case after the Nakba (catastrophe and mass expulsion of Palestinians) occurred in 1948.

Tatreez played an even more vital role now as a means of income for many displaced families, and to further tell their stories in exile.

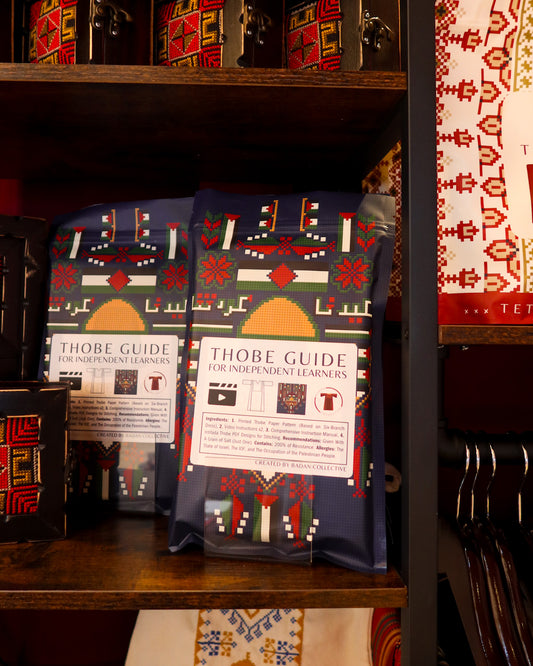

One of the most notable dresses to emerge after the Nakba was in the late 1980's and early 1990's during the First Intifada: The Intifada Thobe—a dress term coined by Widad Kawar. This emerged after the Palestinian flag was banned by the Israeli government to be publicly displayed, and as an act of defiance, Palestinian women took it upon themselves to stitch the flag into their thobes. This was an illegal act at the time and was often done in secrecy. However, it allowed tatreez to take on a deeper role as a form of resistance for the Palestinian struggle for liberation.

This craft only deepens in meaning with time. It can also be viewed as a form of healing and bringing together community for both Palestinians in occupied Palestine as well as those that find themselves in the diaspora. It is a powerful tool—one to be learned and preserved at all costs.

We invite you to preserve it with us. Whether you're Palestinian or not, we encourage all those living outside of Palestine to pick up this craft with intention by attending a local tatreez workshop near you.

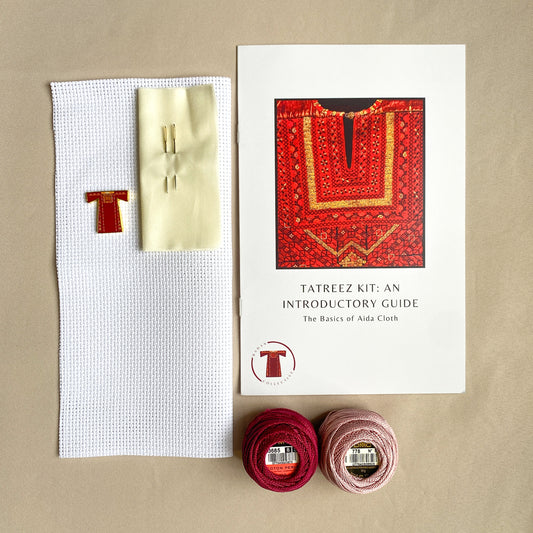

Or, if you're unable to attend in-person, we encourage you to grab a beginner or advanced tatreez kit that will teach you step by step how to participate in tatreez from the comfort of your home.

It is up to us to continue the practice of tatreez and preserve it for generations to come.